Kaha Mohamed Aden

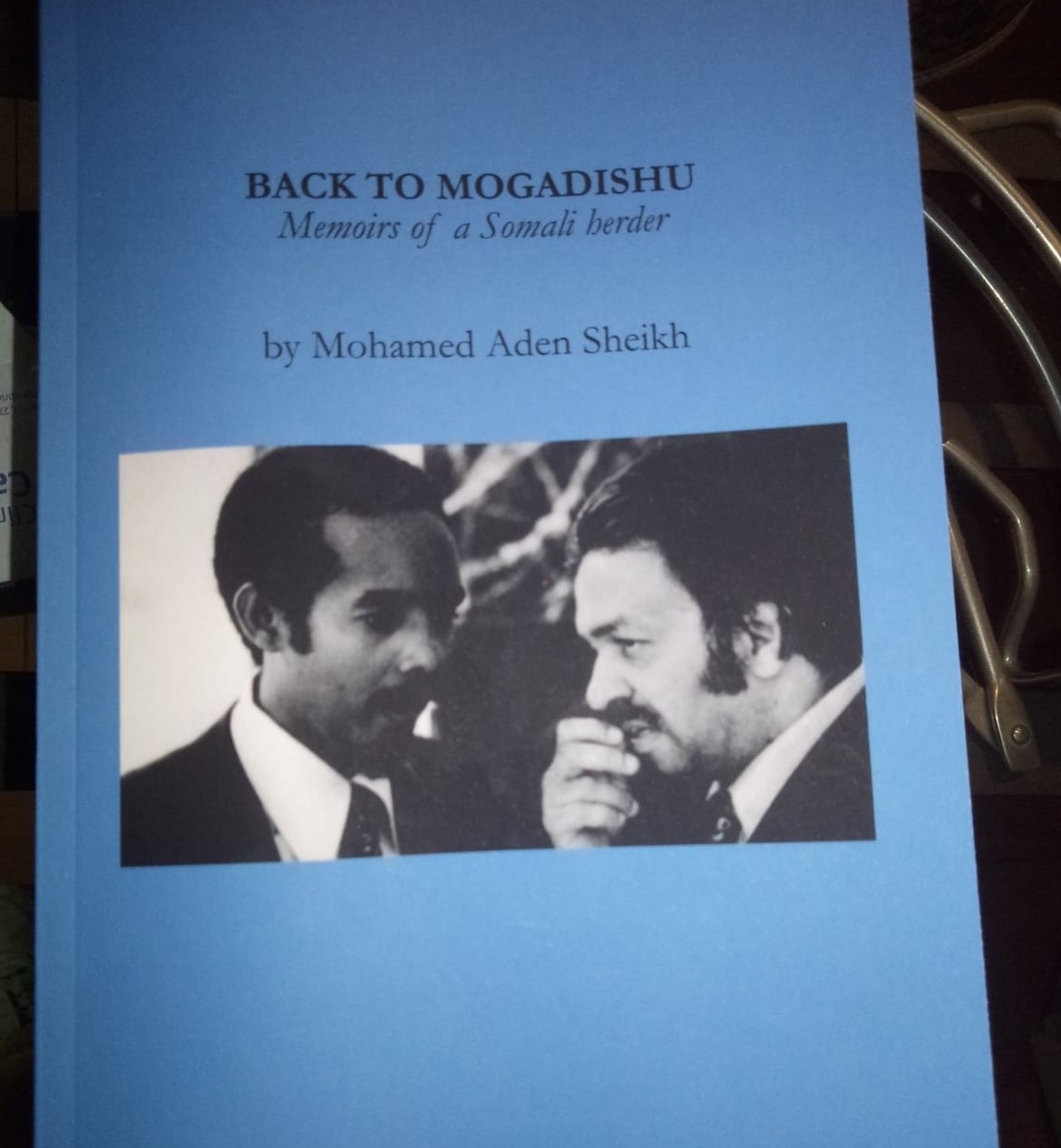

A happy, ungainly flight from the Yaya Centre*

Il titolo originale dell'articolo è Un felice goffo volo dallo Yaya Centre, pubblicato sul numero monografico della rivista «Africa e Mediterraneo» dal titolo Corno d'Africa: prospettive e relazioni. L'autrice guida il lettore attraverso il complesso mondo dei clan somali, denunciandone la degenerazione e le gravi conseguenze sull'attuale situazione somala, alla luce del ruolo svolto da suo padre Mohamed Aden Sheikh. La sua figura di leader politico di una fase storica ricca di riforme poi tradita dalla dittatura di cui fu oppositore sino ad essere incarcerato, rischiava di cadere nell'oblio insieme alla prospettiva di uscita dal caos somalo in modo fortemente critico di quello praticato dai signori della guerra. Il recupero dei suoi scritti, oltre a costituire un materiale utile per gli studiosi della Somalia, è un contributo per restituire una fetta di memoria alle generazioni vissute nel caos della guerra in-civile e quindi private di una visione alternativa allo scontro violento per fazioni.

Kaha

|

|

It all began in 2017, at the Yaya Centre in Nairobi, Kenya, when all of a sudden a young Somali man burst out with the title of one of the two books that my father wrote: Arrivederci a Mogadiscio. What a surprise! After a presentation, the young man mentioned the title so suddenly and unexpectedly, there, at the Yaya Centre - a shopping centre where Somalis in Nairobi go to chat. It's the place where people are introduced and arrange to meet, where you go to look at others and have others look at you. Discretely, of course. People go to the Yaya Centre to fill each other in on the latest news, to gather information about Somalia or to get an update on the most appealing business deals of the day. The Somalis there behave more or less as Somalis have always behaved, since ancient times, turning the very urban Yaya Centre into one of the wells which nomads would gather around to water their camels and exchange news about the best pastures and the latest poetry. Just as the nomads gathered in small, homogenous groups, according to age or clan as they waited for their turn to water their camels, so we, to quench our thirst with the magic of gathering peacefully, split up into small groups, according to clan, age or business interests. I am a guest at a Majeerteen table. The head of my table belongs to this subclan of the larger Darood Clan.

«Who is this lady?» a long, long man in his sixties asks the head of the table.

«This is Kaha Mohamed Aden», then, to better explain our connection, the head of the table adds that he is my adeer - my paternal uncle.

«Her adeer? So her father is Mohamed Aden Sheikh? The Marreehaan doctor?» asks the long, long man again, underlining a difference between us with a smirk. In fact, the Marreehaan - the subclan which my father belongs to, as do I, given the Somali patriarchal family system - are also a subclan of the Darood, but a different one from that to which the other people at the table belong, including the only other woman present. The Marreehaan and the Majeerteen are two branches of the same Darood family tree.

Clan etiquette dictates that, when in a homogenous group - all Daroods, for example - you should joke about, and perhaps exaggerate, the differences between the members of the group. That's why, at that table of Darood clan members there in the middle of the Yaya Centre, the long, long man dared, half joking, half serious, to place me in my separate subclan with his rhetorical question. There has always been a reciprocal antipathy between cousins from these two Darood subclans. However, since the beginning of the war in 1991, all Darood have been attacked and hunted together, because they are Daroods. So, they have had to come together, create alliances and overcome their reciprocal "antipathies". Fighting against them in this conflict was the great family of the Hawiye clan.

The Hawiye, according to the self-proclaimed "representatives" of the clan, have always maintained that from the beginning of independence in 1960, Somalia was dominated by the Daroods. They say that in the first nine years, in the famous "democratic" period, the Majeerteen held power. In fact, there is a Shirib1 by a Hawiye activist, which was very popular at the time and which criticises the president of the Republic, Aden Abdulle2 for allegedly not having correctly carried out his task of nominating the prime minister. In two successive administrations, the president had chosen two Majeerteen men, one after the other. The Hawiye clan militants probably expected the president to make a different choice. The Shirib poem ironically says:

Marna Rashiid

Marna Rizaaq

inta kale ma rootiyaa?

Once Rashiid3

Once Rizaaq,4

Are all other Somalis soft bread?

The president is clearly and provocatively asked whether he thinks there are no men worthy of the role in other clans. Why choose only Majeerteen men to lead the government? So, going back to those who proclaimed themselves "representatives" of the Hawiye clan: from the beginning of independence, after nine years of Majeerteen rule, on 21 October 1969, there was a bloodless coup d'état led by Siad Barre, which was welcomed by the people and power was put in the hands of a man from the Marreehaan - another subclan of the Darood. "It was about time that the unfair rule of the Darood ended! And that is what we did in 1991. We got rid of the faqash,5 the swine, kicking out the Darood from our land", say the self-proclaimed spokesmen of the entire Hawiye clan.

There have always been rivalries and conflicts between clans regarding the natural resources that their lives depended on. The conflicts have also been long and cruel, but besides this, there was also a set of customary rules and a system of constantly mutating alliances. Considering the state on the same level as natural resources and seeing the other clans (masked as political parties) as rivals in the battle to conquer the state is an idea which was born at the end of colonialism in the hurry to establish a democratic state in order to achieve independence. It was a process in which the colonialists and their collaborators were heavily involved. The end result was such a mishmash that it did not even contemplate a census or any attempt to modernise the tools which traditionally regulated conflict. The independence forces approved the project in order to rid themselves of the colonialists. When Siad Barre later came to power after a coup, in order to hold onto his power he did not hesitate to take advantage of the same concept of a state, manipulating the clans through repression and clientelism. Then, in 1991, when the Somali state imploded due to its clan conflicts, fighting for its control was no longer urgent for the clans. There was no state anymore! What concerned the men at the head of the winning clan was to free themselves of the institutions and, with them, of the rules - all rules, be they modern or traditional, so as to be free to do as they wished. Naturally, access to public and private resources was exclusively reserved for them and their clan. Pushed forward by the tailwind of chaos, the clan organisations began to see one another as enemies. This atmosphere led to each clan, unfortunately none excepted, being led by people with no scruples or sense of responsibility. Initially, after the dictator had been overthrown, anybody who was of the wrong descent and did not want to end up killed - or at the mercy of the militia - had to flee, starting from the Daroods. So, here we are in Nairobi, a happy, tranquil bunch of Daroods in the pleasant, fresh shade of the rules guaranteed by the Kenyan state. We have already mentioned that traditional clan etiquette requires differences to be underlined when there is a homogenous group. Well, etiquette also dictates that at a certain point similarities, relations and closeness among the subclans and clans of the present be mentioned. No one should be cornered as the majority group would lose some of its prestige. This "turn taking" is currently little practised as it is linked to stability, good neighbourliness and peace. In order to correctly follow protocol, we need to leave the surface of the tree and go deeper. There need to be not only notions, but a culture which conceives the need for peace; something which is so strongly rejected by the current Somali spirit. We spent some time playing on the surface of the tree. Of the various branches originating on the Darood tree trunk, the Majeerteen limb was explained to me from top to bottom, in and out, right up to the leaves in the crown. Someone even tried to explain to me that, grazing the camels of our respective patrilineal segments together, the corresponding twigs on the great Darood family tree intertwined nicely. All this was for me the blurred foliage of an abstract tree that I couldn't bring into focus, but in the end I learnt a few notions.

Our game on the tree surface and in the branches of the family tree continued until another man intervened. This gentleman was a little shorter than the beanpole and around seventy years old. According to the rules of this "dance", his intervention means we must change steps. We dig down underground, we're going deep this time. The man names two ties which link the Majeerteen (the majority clan of this table) and my father's clan. These ties, called Hidid, are inter or intra-clan marriage ties embodied by women. Naturally, they are not marriages which are arranged for the good of the women, but for the good of the clan. Their aims were to restore and maintain peace. It is well known that nearly all trees have an outside part made up of branches, leaves and a trunk, but they also have an underground part: that of the roots, which ties them to the ground and gives them essential nutrition. Down into the roots we go at times of crisis to reactivate wholesome contacts through women. The man looks straight into the beanpole's eyes and mentions my paternal grandmother's name, Suuban Bootaan Shabeel. He immediately says that she is a Majeerteen woman. Essentially, he is telling this small Majeerteen assembly that Aden Sheikh is the son of one of their daughters. Then he makes a face as though he's just had a thought. Silence. Then he says that either in the first book or in the second, in one or the other in any case, Doctor Aden did not forget to write that the failed coup against the dictator, led by the best of their men - Colonel Mohamud Sheikh Osmaan,6 aka Irro, had also been carried out in revenge of the repression of the Majeerteen in the Mudug region.

«See, although the Doctor belongs to the same subclan as the dictator, he didn't forget to point out the wrong done to us!». Then he adds, «You know that the Colonel and the Doctor are first cousins on the former's mother's side, don't you? The Colonel's mother is the Doctor's paternal aunt, Mrs Khadija aw Mohamud!».

This man was leading the dance at the time and did what was required of him in his role, in other words re-joining what had just been separated, and, by the simple act of naming the two women, he essentially cleared up the fact that even though my father belonged to another branch of the Darood clan, deep down, he wasn't all that far from the Majeerteen branch. While all this is happening, a third man enters the scene. His accent is neither Hawiye nor Darood, but strongly Mogadishan. In fact, we can tell that he belongs to the Reer Hamar clan - the people of Mogadishu, as Hamar is the other name for Mogadishu. They too are a minority which has been expropriated and expelled from their own city. Not to mention massacred.

«I know her, she's Yusuf Marreehaan's granddaughter!». Says the third man, and begins to speak about Granddad Yusuf, who was his neighbour. He explains why my grandfather's nickname is the name of an entire Darood subclan. At the time, he says, Yusuf Marreehaan was one of the most authoritative of this branch of the Darood clan, a long time before they even knew of the existence of Siad Barre in Mogadishu, he adds ironically. He had another nickname too: "amm Yusuf" - Uncle Yusuf was what members of the Somali Youth League7 called him. In fact, he was a senior member and mentor in the League. The third man speaks about the "Aw Mohamuud" family in which Granddad Yusuf was the eldest of a group of brothers who arrived in Mogadishu from the bushes. Nomads. A family who all belonged to the Somali Youth League and were cultured scholars of the Koran and later on, some of them took on important roles in the various governments that Somalia had over the years. Many stories could be told about this family, but there is a distinctive trait that this gentleman did not fail to mention: the family cared about the education, and therefore the independence, of its girls. Starting with Granddad Yusuf, everybody fought for their daughters to go to school, never losing sight of the importance for other girls, others' daughters, to have an education. All the girls in the Aw Mohamud family received an education and at the end of the 1960s there were several women with degrees in the family, says the man.

Something's not right!

Because, even when my father is described in such detail as to be identified not just as belonging to a generic Marreehaan subclan, but as a member of a specific family of that clan, a family which enjoyed its autonomy, its prestige and its resources, a family which didn't need Siad Barre to have its position in society, even after all this, why is it that no one mentions his role as a political leader? He was the leader of a group of intellectuals who were from different clans, but who were united in following a project of modernization and emancipation of their country and who wanted to set out on their own Socialist road. In these times of mental regression in which, be it out of necessity or opportunism, the focus is always on clannish relations, whenever my father is described there is no risk of hearing mentioned the cholera-vaccination campaign or the writing of the Somali language, the literacy campaign or the establishment of the Somali National University: these are some of the projects to which my father dedicated himself, with the support of all Somalis. Nor is there ever a trace of the time he threw himself into promoting the process to democratise institutions because he believed it was unacceptable for the army to have a free hand in the power and direction of the state. This was why the regime, led by Siad Barre, reacted by locking him up and throwing away the key. Under Siad Barre, my father experienced prison twice. First for nine months in 1975. The second time, he was imprisoned from 1982 to 1988 - six long years of isolation in the Labatan Jirow maximum security prison. In addition, he was under house arrest for all of 1989. This, however, was a walk in the park for Dad compared to the isolation he had been through.

My father clearly wasn't familiar with the idea of obedience. What's more, the reaction of the regime was predictable, given my father's keenness and his political and social fervour. What I still cannot comprehend, however, is why at meetings like this one at the Yaya Centre, where there is a keen clan mentality and people are capable of seeing the tiniest connections in the complex web of Somali clannism, it is never mentioned that my father's belonging to the same subclan as Siad Barre, head of the regime, was of no aid to him. Perhaps because admitting this fact would destroy the weak pillars that prop up clannism? On the other hand - and it's not the first time that it's happened - I am more used to the fact that everybody wants to skip a precise moment in Somali history: the Seventies, or at least the beginning of that decade. It was precisely in that period that the head of the table entered my life and became my paternal uncle, as did others - including a Sicilian - at different times and in different contexts. The head of the table is part of that group of civilians, the then ruling class of Somalia, who, with my father, had dreamt of being self-sufficient for food, and of education for everybody; trying to avoid getting into debt with other states and organisations, or moving away from traditional culture. It wasn't an easy dream to make come true but they had worked hard and turned some of their ideas into projects and despite their arch rivals, the army, they had managed to reach some important goals, to the point that still now, not even their fiercest detractors can deny it. However, they try not to talk about it, to hush it up. The head of the table doesn't take part in any of this conversation. He is quite simply happy to see me again and to have me there as his guest. I am happy to have met him again, although…

«Excuse me, madam».

«Excuse me, madam!». Again.

Someone is calling me and at first I don't hear them, perched as I am on the twig which, according to the decrees of the reigning clannism, corresponds to my immediate family, and, to be honest, lost as I am in the melancholy which always overcomes me at these meetings. It is sad to realise how little those moments count in which my father paced his tiny cell alone, in the dark, for years and years, day after day. And for what crime?!

Someone touches me on the shoulder. Now I can hear him. It's the boy who came out with the title of Dad's first book at the beginning of this story. He's been calling me for a while and now he finally has my attention. He is holding a pen and a paper napkin which he took from the napkin dispenser you find on café tables. He asks me to write the title of my father's second book, which he has just heard about in my presentation. La Somalia non è un'isola dei Caraibi, I write.

«But, is this in Italian too? No one reads Italian anymore!». Says the boy, disappointed.

I look at him in silence as if to say, "What can I do about it? Those books are in Italian!". And with that attitude, I think I have avoided the matter. Perhaps I am afraid of the mountain of work needed for a translation, should I have to do it.

«Why don't you translate it into English?», he asks. «All the diaspora and lots of people in our country, too, read English», he insists.

Even though it scares me, listening to his request fills me with joy because this boy is the ideal reader for my father's books and, seven years after the publication of the second, he is asking to be able to read it. It would give him the chance to understand that this briar patch of families and their family trees has nothing to do with the traditional way that clans organised themselves.

He would find out that today's clannism is just a simple way of UN governing Somalis and their land, given that today's clannism is an end in itself and has thrown out the culture, the rules with which the clans traditionally self-governed and looked after people and the environment. The perverse will of the new lords of Somalia - the lords of the clans - for defection from the rules is confirmed by one simple, practical, environmental example. A document by UNEP,8 the United Nations Environment Programme, declares that the current deforestation in Somalia is due to the lack of laws that look after the environment and, therefore, the people. The document states that the market value of Somali charcoal exports - that is, the export of trees which have been cut down and burnt - is estimated to be around 250 million dollars, just for the two years following the prohibition of its sale. What's more, it is worth noting that in order to mitigate the rampant desertification of Somalia, it was necessary for an external organization - the United Nations - to ban Somali charcoal exports in 2012.9 Furthermore, in 2016, three United Nations agencies launched a joint programme10 to promote international cooperation in supporting the ban and to "ensure" that we Somalis understood the disasters that would follow the destruction of our ecosystem. Apparently the heads of the militias, of any militia, with their big-shot friends, turn a deaf ear. They always find a way to get around anything that impedes the activities that have led to 2.1 million trees being cut down each year since 1996.11 For these lords, rules and laws are obstacles to the constant flow of dollars and to their freedom not to have to share the revenues 12 or the social costs of their decisions, which actually fall on others, not least the members of their clan who they boastfully represent.

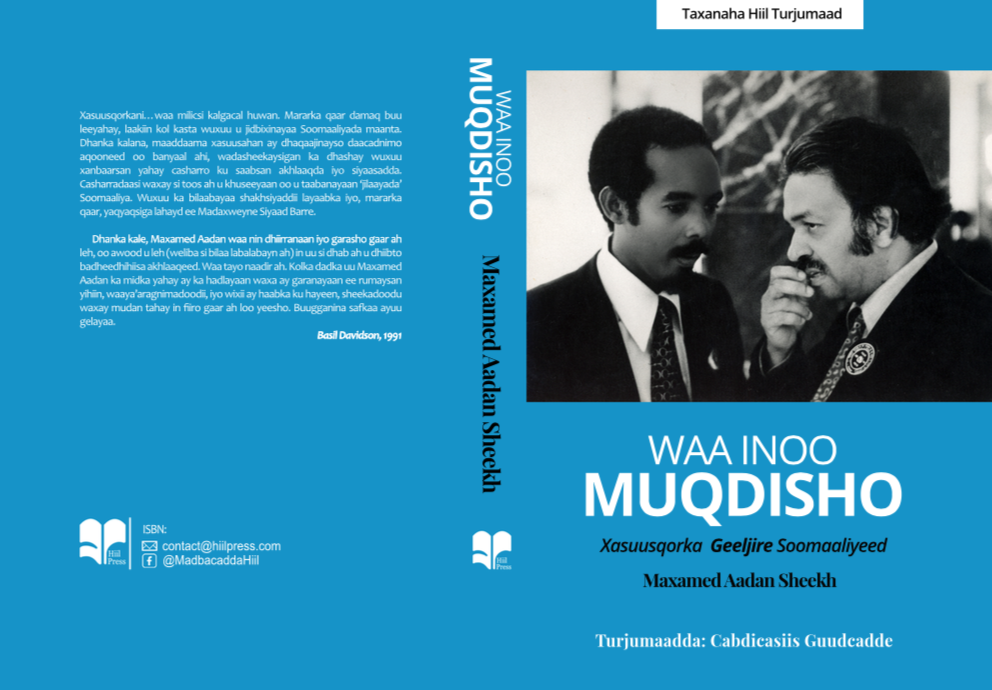

Yes, on second thoughts I would like the boy to know how innovative the Ba'ad Elin programme against the desertification of our savanna was. An English translation of my father's book would allow him to discover that at the beginning of the 1970s trees were being planted in Somalia to create green barriers,13 without the need for the United Nations to come and explain to us that getting stuck in a barren desert, with all that this implies, is not in our interest. I decide to take on the task of the translation. At the end of the day it's an old wish of mine too. I would like to call the whole work "Back to Mogadishu". I would also like to translate it into Somali and call it "Waa inoo Muqdisho". Why not?

I've always toyed with the idea of letting the world see the Somali affair through the eyes of my father and I have also always thought that certain events need to be accounted for. Essentially, I realise that this boy is giving me the chance to fly from the twig to which I have been relegated. Around three o'clock, having been treated like a princess by my uncle, having eaten my lunch and drunk my spiced tea, feeling a little weighed down by the worry of "How the devil am I going to honour my commitment?", but happy, I launch into an ungainly flight and leave the Yaya Centre.

Bollettino '900 - Electronic Journal of '900 Italian Literature - © 2023

<http://www.boll900.it/2023-i/Aden.html>

gennaio-maggio 2023, n. 1-2